Review

All lectures are freely available on this site.

THE CONCEPT OF THE SOCIAL – Remarks on Schmitt’s Political and Ibn Khaldun’s ‘Asabiyah

As Salamu ‘Alaykum.

In the name of Allah, All Merciful, Most Merciful.

Blessed is He who taught Adam (peace be upon him) the Names and who has placed mankind as a trustee over the universe.

Glory be to You! We have no knowledge except what You have taught us. You are the All-Knowing, the All-Wise. (Quran 2:32)

Ibrahim was a community in himself, exemplary, obedient to Allah, a man of pure natural belief. He was not one of the idolators. (Quran 16:120)

Before I begin this discussion in earnest, let me say thanks to Mark Barrett who organized the event, Abdassamad Clarke whom I initially approached about giving a talk, and ‘Uthman Morrison who recommended changes to earlier drafts and who also helped me harmonize earlier ideas I had for this discussion with the theme of this forum.

P.0 Introduction

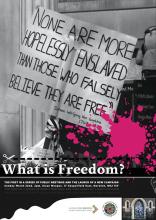

This forum has the theme of freedom. I want to discuss this theme in terms of politics.

Two political view-points will be juxtaposed in this discussion. On one side is the political theory of individualism. Without a doubt, contemporary politics is equated with individual freedom. However, a different perspective will be advanced herein and an understanding of politics will in turn, I hope, point to a different understanding of freedom.

I hope you bear with me, as I will need to enlist the insights of two of the greatest thinkers in the history of political philosophy, Carl Schmitt and Ibn Khaldun, in order to convey to you in the most convincing terms the undoubted relevance to us of this perspective, which is that of freedom as a collective bargain. With regards to these two thinkers, it is also not irrelevant that they represent something that seems almost unimaginable in the current climate of induced political fear; a beneficial convergence, as opposed to a clash, of civilisations

These extraordinary men are separated by approximately six centuries of world history. Yet, they approached politics in a similar manner. They thought of politics as the consummation of community, rather than a means to arrive at individual freedom.

I hope you will accompany me as we are taken through Schmitt’s thoughts on the political, on through a most constructive critique of one of Schmitt’s most famous books, then on to Ibn Khaldun, and ending with a new evaluation of the political as distinct from the social.

P.1 Carl Schmitt & Legal Order

Carl Schmitt was one of the great jurists of the last century. To say that he is controversial is a gross understatement and taking him today as our modern political ‘thinker of choice’ has a direct bearing on the theme of freedom. The relevance and power of his thought is deserving of our attention, controversy notwithstanding.

First and foremost Schmitt was a jurist, a legal theorist. Primarily, he theorized about public law – or that area of law concerning relations between the government and the governed. This led him to speculate on political matters. Above all, he wanted to understand the legal order.

Schmitt’s speculations on the legal order leads him to conclude that law is not autonomous.1 As a very simple example, we can say that the judgement of a judge, no matter how truthful or well-argued, only acquires force because there is a whole apparatus on hand to activate the judge’s verdict. At the same time, Schmitt does not believe in brute force as a means of compelling people to obedience. This is illustrated in one of his most notable books, Political Theology. He cites Jean-Jacques Rosseau. Rosseau had rightly said in Du Contrat Social that the mere fact of a robber having a pistol is no compelling reason to obey the robber.2

From what has been said so far, we may surmise that Schmitt neither denied nor confirmed freedom but that he was a realist. Legality or pure force are to be balanced, it may be supposed.

Disabuse yourself of this notion. Schmitt believes in freedom but instead locates it in the community. What is the currency of collective freedom that relates most specifically to the legal order? It is legitimacy, and legitimacy precedes and ranks superior to legality. Legitimacy is a necessary condition for legality.

Jurists do not legislate what legitimacy should ‘look like.’ They instead legislate for legitimacy, according to Schmitt. This concept of legitimacy means that freedom, true freedom, is not something that can be written down and handed to you on a silver platter – it cannot be manufactured and heated up for you like a microwaved product– because then you are accepting some other community’s version of freedom. By definition, this is not freedom at all for the community who is the recipient of this pseudo-freedom.

But, to link back to politics, there is something even deeper than legitimacy. Legitimacy occurs when a political order is widely accepted by those whom it addresses. Legitimacy exists in the realm of politics. Hence, an understanding of why there is a legal order in the first place rests on an understanding of politics.

And since political life can’t spring up out of nowhere, this means that we cannot understand law without understanding society.

P.2 Carl Schmitt & the Political

The gist of what has been said so far is that ‘Carl Schmitt tried to understand law and arrived at politics.’ At this point, we come to a crucial distinction that Schmitt makes.

Schmitt speaks deprecatingly of politics. Politics means for Schmitt what it means for most of us; an arena of competition between vested interests.3

In The Concept of the Political, one sees that, fundamentally, the State is not what Schmitt is in pursuit of when trying to understand what underpins the legal order.3 Yet Schmitt revelled in extremes and the State remains the most vital manifestation of political life because it can dispose of human life.4 This seeming contradiction will be better resolved in a little while.

What Schmitt is after is the political. That is not one word, but two words. By putting ‘the’ before ‘political,’ Schmitt singles out something and elevates it above all else. Politics implies play and fun between those who only superficially appear as adversaries: the political implies something serious, but also something unique and final. Furthermore, it implies something that must be asserted; a free assertion of will.

Schmitt defines the political in The Concept ... He looks at morals, economics, and aesthetics, and then asks: what essentially are these? If we can know exactly how morals, economics, and aesthetics are defined, we can then define what is exclusively political.

Now, I love those wonderful Mr. Men and Little Miss cartoons and use them to illustrate what Schmitt says here; if you could take the concept of ticklish or grumpy until you had made an absolutely ticklish and grumpy person, what would they look like? Its like Plato and universals. For the moral, aesthetic, and ethical, as well as the political, universals are to be imagined in terms of criteria – for example, what would a moralist, isolated from all other fields of human knowledge, consider the ‘black-and-white’ issues of his domain?

So if we had a Mr. Moralistic, we would have someone purely concerned with good and evil. If we had a Little Miss Aesthetic, we would have someone purely concerned with beautiful and ugly. And if we had a Mr. Economic, we would have someone purely concerned with profit and loss.6

Schmitt then says about Little Miss Political;

The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.7

Schmitt goes on to explain that the enemy may not be an obvious one, likewise with the friend.8 If we consider the participants and alliances of World War I, for example, it is not easy to categorize them into simple religious, ideological, or national, perspectives. Another elaboration is that the political resides at the utmost intensity of association, and the anti-political resides at the utmost intensity of de-association.9 Going back to the earlier point in the discussion about politics and the State, the State is the one identified as being entrusted with the political because it can both dispose of life and choose the ultimate enemy that one kills in war. But the political is yet something different from the State.

Freedom to choose one’s friend, freedom to choose one’s enemy … in a nutshell this is Schmitt’s collective freedom that comes to the fore in his concept of the political. It is definitely a collective freedom because Schmitt railed against politics and the disassociation caused by vested interests.

P.3 Strauss’ Critique

Leo Strauss is another philosopher who, like Schmitt, has been the subject of controversy and probably will be so for some time. He picked up on the theme inherent in The Concept … In particular, he noticed that Schmitt polemicized against liberal individualism, that bastion of individual freedom.

Strauss wrote a critique of the first edition of The Concept of the Political. Schmitt brought out a new version five years later on the back of this criticism. For Strauss, Schmitt’s book profoundly affected his life. Strauss would seek political rationality in the company of medieval philosophers, mainly Islamic and Jewish philosophers, who, Strauss felt, had interpreted the classics correctly.10

A brief digression will illuminate the kernel of Strauss’ criticism of Schmitt. Misanthropy is the essence of modern Liberalism. The individual is being assailed by others and must use whatever means are at his disposal, including playing organs of government off against each other, to validate his own freedom. It is a secular Puritanism. Just as the Puritan wanted to be completely freed of anything standing in the way of his idea of pure worship, the liberal wants to be completely freed of anything standing in the way of his humanist relativization.

Therefore, Thomas Hobbes rightly deserves the title of Liberalism’s founding father because of his anthropology. Anthropology is the scientific study of humans and every political theory must have a distinct anthropology. Hobbes earns his title because he had a conviction that humans are essentially anti-social and he said that man is a wolf to other men. Hobbes is considered the first liberal. That is despite the seeming incommensurability between Liberalism and the authoritarianism Hobbes is famed for.

Strauss picked up on Schmitt’s clear preference for the enemy half of the political criterion.

Of the two elements of the friend-enemy mode of viewing things, the “enemy” element manifestly takes precedence, as is already shown by the fact that when Schmitt explains this viewpoint in detail, he actually speaks only of the meaning of “enemy”.11

Strauss then notes how very similar in form, but not so much in content, this is to Thomas Hobbes. For Schmitt, the natural state of man is to live as packs of wolves, whereas for Hobbes men are lone wolves, i.e. essentially misanthropic. Because of this difference Hobbes does not see it as dishonourable for someone to flee the theatre of war to save his own skin.12 Schmitt, as we have seen, recognizes the right of the State to freely dispose of the lives of its members. Yet Strauss is basically correct about Schmitt when he says that Schmitt remains within Liberalism’s boundaries – he is an heir to Hobbes.13 Man is still misanthropic because he sees an enemy and flees from him towards friends. Presumably, amongst these friends Man can transcend his misanthropy: this seems to be a difference between Schmitt and Hobbes. This assertion is based on the influence of Maurice Hauriou, a French sociologist, on Schmitt during the 1930s. Hauriou perceived of institutions as developing in organic terms, for example from markets. Schmitt came close to Hauriou but did not fully leave behind his earlier more Statist thinking.

So in summary, Schmitt’s critique of individual freedom, delivered in terms of collective freedom, has not fully left behind the foundations of Liberalism, Strauss insists.

P.4 De-politicization/Political Euthanasia

Schmitt enjoys a tempestuous relationship with Hobbes. He understands that Hobbes brought order to the sovereign decision – and Schmitt is a law-and-order man – as much as he understands that Hobbes also helped to de-politicize man by promoting individual freedom.14

This de-politicization I will term political euthanasia. Political euthanasia is not insignificant. Where there are no values worth living or dying for, there are no longer any friends or enemies. Instead, there is only technology, economics and a nebulous version of culture. In other words, there is the Liberal world-view made solid.15 Everything is relativized with respect to the absolute centre of individuals.

In passing, it is interesting to note that political euthanasia often brings with it an augmenting of the State’s power, as evidenced by the near 14 year global state of emergency, also known as ‘The War on Terror.’ The reason for this paradox should become clearer later in the discussion.

P.5 Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun, the 14th – 15th century Islamic thinker, understood politics in a similar manner to Schmitt. Relative to the common strain of Islamic philosophers, Ibn Khaldun was a technician. Practical matters dominated his thought rather than abstractions. Mostly, he was concerned with the rise and fall of Muslim dynasties. His theories of politics, sociology, history, and economics, are presented in Al-Muqaddimah.

Both Ibn Khaldun and Schmitt had the uncanny knack of examining history with a synoptic eye. This skill that they shared in common engenders a sensitivity to historical shifts in the tectonic plates of geo-politics. Both are also able to peer inside the mechanism of history and detect the driver of the historical engine. For Schmitt it was a binary model, the model of friend and enemy. On the other hand, Ibn Khaldun invoked another concept, that which is termed in Arabic ‘asabiyah. First of all, this term needs to be put into context.16

Passing through North Africa, Ibn Khaldun couldn’t help but notice that civilization, or ‘umran in Arabic, was inherently social. Groups of people came together and mutually benefitted one another. This sense of ‘umran is derived from the inclination to culture and to cultivate.17

As opposed to modern geo-political observers, Ibn Khaldun did not see any reason why co-operation needed to be constrained by resources. Why, in that case, he wondered, did some communities grow larger than others? What made some communities grow at the expense of others?18

To explain such differences, Ibn Khaldun invoked ‘asabiyah. There was a strong implication of family ties in the very word itself, but Ibn Khaldun did take pains to ensure that ‘asabiyah referred to the instigation of a group feeling above all else. For Ibn Khaldun, domineering civilizations were phoenixes that rose on the uplift of ‘asabiyah.

Despite his innovative terminology, Ibn Khaldun retained a very classical understanding of the political. In his prefatory remarks to chapter I of The Muqadimmah, Ibn Khaldun discusses the political. Here, the political is discussed purely in terms of its classical roots. The Greek word polis is used explicitly, for example. In contrast to modern day connotations of the term, the political is not employed as a technical instrument that shapes disparate groups. Rather,

Man is `political' by nature … he cannot do without … social organization.19

Ibn Khaldun goes on to mention logical reasons that necessitate civilized behaviour.20 He is invoking this ‘umran or culture. In agriculture, foodstuffs are being cultivated, in horticulture, plants, so what is being cultivated in the polis?: human nature.

A key passage is in chapter III of Al-Muqaddimah. Ibn Khaldun declares that

[r]oyal authority and large dynastic (power) are attained only through a group and group feeling. This is because … aggressive and defensive strength is obtained only through group feeling which means (mutual) affection and willingness to fight and die for each other.21

Such a sentiment clearly smacks of Schmitt’s musings in The Concept of the Political.22 There are subtle differences, however. Schmitt defines collective freedom with respect to the ‘other,’ namely the enemy. Ibn Khaldun says that this collective freedom emerges from the political, i.e. after this cultivation of human nature, and is a group feeling which asserts its superiority over others. Interestingly, Ibn Khaldun even discusses sovereignty in very similar terms to Schmitt.23 Although it is often associated with a powerful individual, sovereignty is in fact the mark of a collective will to act, I wish to stress.

Principally, the views of both thinkers strongly imply that freedom, collective freedom, is relative to something else. That is why there can be no such thing as individual absolute freedom or Robinson Crusoe freedom. Such freedom is not free with respect to anything. Instead, there is a human state of being that profits from the ‘free’ foundations that collective freedom has laid down, whittling away these foundations in the process.

It is of significance that Schmitt had avoided falling into the trap of equating the State with the political.24 The political is something other than institutions, as it is for Ibn Khaldun. It relates to identity. It relates to an Us. This is also a classical approach. When Aristotle mentions the fact that man is a political animal in book one of The Politics, it is preceded by discussions of family and of community. What mattered for Aristotle was the social, not structures or institutions. Pocock tells us that Aristotle harboured a fear that democracy would become

a system in which all power was exercised by mechanical, numerical majorities, and only those goods taken into account which could be discerned on the assumption that all men were alike. Such would be a tyranny of numbers and a tyranny of equality, in which the development of individuality was divorced from the exercise of power, what a man was from what part he might play in politics. Aristotle was anticipating features of the modern concept of alienation, and there are elements of this criticism of undiscriminating equality in present-day criticisms of the depersonalizing effects of mass society.25

To avoid lapsing into such tyranny, to avoid an absence of collective freedom, there must be social development and a shared civilization. Note that this runs counter to the Liberal view of freedom which tries to institute structures that will guide individuals on their quest for solitary freedom.

P.6 The Concept of the Social

Back to our Mr. Men and Little Misses. Now I disagree with Schmitt when he says that morality is about good and evil, but I agree with him about his criterion of the economic and the aesthetic. I will use this type of criterion to arrive at a clearer definition of the political. So, for example, profit and loss are two ‘states’ of the realization and the negation of economic activity, respectively.

Schmitt’s criterion of the political seems inadequate because it describes those who participate in the political as opposed to the two states of the political and anti-political. Furthermore, an enemy may find use in promoting a political cause.

I had thought of defining the political in terms of the absolute and relative; the political relativizes everything else. But this relates to value. Values strive to be absolute. Relativization is the enemy of value.

To arrive at a criterion of the political, I imagined a very political event that strikes as vivid a chord as possible. What I imagined were the IRA prisoners who went on hunger strike in the 1980s. In particular, I imagined them sleeping in their own faeces so as to earn the name of the political. It is something that I can imagine but also something that I can’t imagine. That makes it a worthwhile image.

The criterion, I conjecture, is that of defiance and acceptance. The truly politicized defies everything. When some entity is de-politicized it accepts everything. That ‘everything’ is the status quo. The political defies or accepts the status quo. Even if someone or some group is in power, they defy the status quo and strive to change things if they are politicized. The Middle Ages were apolitical because the status quo, save for events like the Magna Carta which brought about a new status quo, was accepted.

This definition of the political can be attributed to individuals as well as to groups and can even explain the intensity of political violence because the amount of defiance depends on how politicized people are in relation to the status quo. In the realm of the political, you are either hammer or anvil … you are either brake or accelerator.

Schmitt conflated the political, as the word is understood nowadays, with the social. Ibn Khaldun did not make this mistake because he was thinking in terms of the polis when he was imagining the political. At the same time, his ‘asabiyah is an emergent phenomenon that depends on the content of the political and group-feeling enables a community to assert its freedom with respect to others. In our modern day usage, the political, in old money, is the sociological, the cultural, and the civilizational. The contemporary political relates more to the assertion of ideology.

This definition of the political is surprisingly close to what I would consider to be a criterion of philosophy. Philosophy’s criterion would be scepticism and acceptance. Where did politics and philosophy meet and completely defy the status quo? The Enlightenment: and this era gave birth to modern politics. One of the shrewdest observers of these momentous events at the time, De Maistre, classified the French revolution as being a

fight to [the] death between Christianity and philosophism.26

The political is related to the social in the same way that a medical drug is related to the sick person. A sick person has the analogy of a society either slipping into a state of relative values or one under military threat. The political is a drug that can revive it. Political ‘drug-addicts’ are those like the French Revolutionaries of totalitarians of the 20th century who seek to politicize everything to achieve a constant political high.

To go back our 14 year state of emergency, a collapse in social values calls forth political drug peddlers, invariably minority interests who are distanced from the community. Those who ‘pop’ the political drug hallucinate and see enemies where there are none. A culture of fear becomes addictive because it is a habit. And habits are hard to kick. No matter what measures are taken, these measures will not be enough to sustain the political high.

‘Negative-proof’ ideologies will face down these political peddlers. These will be as politicized as the original political drug-addicts, but will invert their ideas. Romantic-type ideologies did this at the turn of the 19th century, whereas anti-rational political Islam does this nowadays.

Let’s get back to the positive vibes of meaningful social relations before I wear out a metaphor. The social is a necessary pre-condition for the political. Society precedes politics. Friendship and enmity, association and de-association, identity and disparity, are criteria of the social. They describe the content of the political but not the political itself.

Carl Schmitt and Ibn Khaldun are crucial in understanding this content which in itself may not be political in nature. Whether the social has a political element can only be revealed by events. The social then either accepts or defies the status quo, in the latter way becoming political, and earning the title of political ‘asabiyah.

Liberalism remains political because liberals will defy everyone to make the individual the absolute centre of existence. An interesting clue to the ethic of Liberalism resides in the oxymoron ‘liberal democracy’: liberals form an alliance with democracy, the latter being a collective phenomenon, to validate their own individual freedom – a very Epicurean policy. Yet, as said earlier, Liberalism remains misanthropic. Instead of saying there is no such thing as a liberal politics,27 it may be more correct to say that there is no such thing as a liberal concept of the social. There is no such thing as a collective freedom in Liberalism as there is with Schmitt or Ibn Khaldun.

P.7 Final Thoughts

By attempting to free the individual, Liberalism attacks the social. But the free human does not spring up from the death of society, anymore than a legal order will spring up if a legitimate authority is brought crashing down. Individual freedom is an illusion that appears when there is a strong social ethic. When these bonds are broken, or when the umbrella of the political is removed, it is revealed that the tranquil environment of the individual – the theatre of personal freedom – is in reality an assertion of collective freedom.

By no means is the ethic of collective freedom the death of plurality. Let me make a scientific analogy to fully explain what a plurality signifies. Plurality and its relation to unity is as a beam of light streaming from a source. There are diverging rays of light, but the rays of light are all ‘in it together’ and all emanate from a common source. This is a suitable metaphor for a common identity. All diverging rays are bound up in the light. They are not haphazard or disparate.

An objection like that of John Stuart Mill can be pre-empted with regard to collective freedom. Mill warned against the ‘tyranny of the majority.’ Yet, a de-politicized sphere enables tyranny to flourish. Germany experienced this in the Weimar period. National Socialists came to power during a highly liberal period of German history.

Living here, one knows about the sense of alienation that life in today’s modern democracies engender. Death is meaningless, life is meaningless. There is no entertainment because there is constant entertainment. There is no love, because there is nothing but love. There is no laughter, because there is nothing but laughter. There are no tears, because there are nothing but tears. While we can access the instruments of enjoyment or leisure, which are the apparatuses of manufactured, individual freedom, we are not free. We are not picking out the particular things that help forge a common identity and a collective plurality.

Ancient philosophers, whom both Schmitt and Ibn Khaldun were indebted to, understood that the polis arose from social love, or what may be called friendship or association. Cicero, the great Roman statesman and enemy of the Epicurean and sovereign dictator Caesar, wrote much about collective love. Plato, whom Cicero was closest to philosophically, gave his name to a form of love.

What was this love, which was deified in the form of Eros? A clue is in the life of Socrates: Socrates shunned all material goods, considering them to run contrary to the spirit of the polis. Yet, he was not a loner. Socrates feared that mere artisanship would nurture a spirit of materialism and would drive the polis away from beholding the eternal, Divine love.

A political euthanasia has lead us away from social love. Instead, we have all become libertine Robinson Crusoes in our concrete islands. We have become de-socialized, or de-politicized in old currency. But personal existence is not that of the individual, it is that of the community. Robert Filmer, the most maligned Divine Right theorist of the Renaissance, had copped onto this basic fact 350 years ago.

Freedom for Schmitt is in the freedom of people to stake out their political existence. For Ibn Khaldun, the development of civilization and sedentary life is something that opens up the gates of freedom. Schmittian freedom and Ibn Khaldun’s polis are collective bargains.

Freedom cannot be handed to you on a plate or manufactured for you. There is no list of essentials that, when acquired, give you freedom. This is an industrialist version of freedom. Freedom is only that of the collective, only that of the community. It can only be acquired by social activity. Hence, the community is the realization of freedom, not its antithesis.

Hajj Idris Mears pointed out that the German sociologist Tönnies made a distinction between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft; the former approaches Rosseau’s version of democracy. Here there is so much agreement between parties in a case to the extent that all want the same thing. In Gesellschaft civilization laws are not sacred and there is a rat-race. As Hobbes recognized, such Gesellschaft requires the firmest exaltation of the State. And this is the death of collective freedom, which it is argued, is really the only freedom it is worthwhile speaking about.

Just to make clear, I don’t want to erect a conceptual structure called ‘society’ where we can all be ‘free’ once we enter into it. This is the industrialist, manufactured, version of freedom. Man is ultimately responsible to Allah: that is the ultimate personal freedom which also carries with it personal responsibility. In the polis – which encompasses all things but is not of them – there is another rule central to both Christianity and Islam, the sources of sacredness that our greats adhered to. And that is to love your neighbour. Don’t love abstract universal ideals that you know that can never be reached so as to make yourself look good in front of others. That is the ethic of individualist Liberalism. Merely love your neighbour. By entering into this social bond, we can avoid the twin traps of political euthanasia or philosophy run rampant.

In conclusion, I would say that it is of vital importance for society to be understood in classical terms, maybe even in terms of the medieval philosophers that Strauss was so fond of reading about. Otherwise, we will have more of the same … and we will deserve more of the same.

Wa ‘alaykum us salam.

References

1. Carl Schmitt and the Problem of Legal Order: From Domestic to International Thalin Zarmanian Leiden Journal of International Law 2006 No. 19 pp. 44-45.

2. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) University of Chicago Press Chicago 2005 pp. 17-18.

3. The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 22-24.

4. Ibid. p. 19.

5. Ibid. pp. 45-46.

6. Ibid. pp. 25-26.

7. Ibid. p. 26.

8. Ibid. pp. 26-27.

9. Ibid. p. 26.

10. Carl Schmitt, Leo Strauss,and Heinrich Meier: A Dialogue Within The Hidden Dialogue E. Robert Statham, Jr. Fall 1998 Political Science Reviewer pp. 209-240.

11. The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 p. 103.

12. Ibid. pp. 105-108.

13. Ibid. p. 122.

14. The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes: Meaning and Failure of a Political Symbol Carl Schmitt (George Schwab and Erna Hilfstein (Trans.)) Greenwood Press Westport, Conn. London 1996 pp. 55-57.

15. See a speech that Schmitt gave in Barcelona in 1929 entitled The Age of Neutralizations and De-politicizations in The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 80-96.

16. Just to make clear: The reference source is; The Muqadimmah Abd Ar Rahman bin Muhammed ibn Khaldun (Franz Rosenthal (Trans.)) Princeton University Press Princeton 2004 Accessed from Scribd.com. Page numbers are from the pdf version where the table of contents is page 2.

17. Ibid. p. 850

18. Ibid. p. 851.

19. The Muqadimmah Abd Ar Rahman bin Muhammed ibn Khaldun (Franz Rosenthal (Trans.)) Princeton University Press Princeton 2004 p. 87.

20. Ibid. pp. 87-88.

21. Ibid. p. 205.

22. For example, see The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 28-30.

23. The Muqadimmah Abd Ar Rahman bin Muhammed ibn Khaldun (Franz Rosenthal (Trans.)) Princeton University Press Princeton 2004 p. 88.

24. The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 p. 19.

25. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition J.G.A. Pocock Princeton University Press Princeton 1975 pp. 72.

26. Considerations on France Joseph de Maistre (Richard A. Lebrun (Trans.)) MacGill-Queen’s University Press Montreal & London 1974 p. 85.

27. The Concept of the Political (Expanded Edition) Carl Schmitt (George Schwab (Trans.)) The University of Chicago Press Chicago 2007 pp. 70.