Review

All lectures are freely available on this site.

1. Story and History

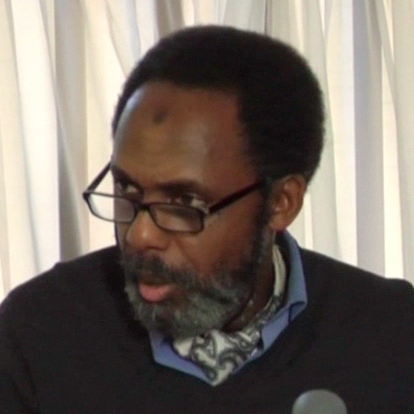

31st Aug – Introduction – Story and History – Uthman Ibrahim-Morrison FFAS, Warden of MFAS

The primary intent is to explore the influence of the story form on the shape and character of human society. There is a self-evident connection, therefore, to the overarching objective of the module as a whole, which is to examine how our literature provides us with an opportunity to gain useful and beneficial insights into our current social predicament by looking at society through the fearless and uncompromising lenses provided by authors and poets.

Warden: Uthman Ibrahim-Morrison FFAS

Warden: Uthman Ibrahim-Morrison FFAS

Uthman Ibrahim-Morrison was born to Jamaican parents in London and studied law as an undergraduate at UCL before going on to pursue postgraduate studies in applied linguistics at the University of Kent at Canterbury. He became Muslim in 1987 and had a leading hand in the establishment of the Brixton Mosque in South London in 1990. He became founder Chairman of the Blackstone Foundation educational trust in 1993 and presently lives in the city of Norwich as a prominent member of the well known Ihsan Mosque community, where he has been occupied with specialist teaching, writing and publishing since 1995.

In his dual capacity as Chairman and Director of Education of the Blackstone Foundation he has played a key role in the development of innovative scholastic initiatives including the Norwich Academy for Muslims, the Wazania Academy for Girls, New Muslim Initiatives and most recently, the Muslim Faculty of Advanced Studies. He is a visiting lecturer at the Dallas College in Cape Town and has regularly presented papers on Muslim schooling at educational conferences and colloquiums. He has also written extensively on the impact of Islam on the modern politics of African identity: Trade First (1996) and The Forbidden Dialogues (1997).

32A • Civilisation & Society 3 • Society Through Literature • Lecture 01 • Story & History • 31.08.13 from The Muslim Faculty on Vimeo.

First lecture in the Society through Literature module of the programme Civilisation and Society.

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم وصلى الله على سيدنا محمد وعلى ءاله وصحبه أجمعين وسلّم

Title: Introduction - Story and History

Author: Uthman Ibrahim-Morrison FFAS

Publication date: 31st August 2013

Assalamu alaykum. Welcome to the Civilisation & Society Programme of the MFAS. This is the first of 12 sessions which make up the Society through Literature module. The entire session will last approximately 1 hour and comprise a lecture of around 40 minutes, followed by a 10 minute interval, and ending with a short question & answer period. You are encouraged to make a written note of any questions that may occur to you for clarification after the lecture.

The Faculty website states our main objectives as follows:

The Muslim Faculty of Advanced Studies is an academic fellowship organisation whose participants are actively engaged in study, teaching and research with a view to identifying the roots of modern society's systemic disorders and planning for the application of the knowledges and practices vital to the attainment of civic recovery and renewal. To this end, our particular emphasis on the juxtaposition of the highest of western intellectual tradition with the most penetrating of contemporary Muslim scholarship continues to bring valuable new perspectives to the fund of knowledge and understanding available to academics and policy makers.

Bearing this wider objective in mind, the aim of this lecture is twofold; both aims are important but one I consider to be primary and the other one secondary:

i) The primary intent is to explore in an introductory fashion the lecture’s own specific theme, which is the role and influence of the story form in the character and shaping of human society. There is a self-evident connection therefore, to the overarching objective of the module as a whole, which is to examine how our literature provides us with an opportunity to gain useful and beneficial insights into our current social predicament by looking at society through the fearless and uncompromising lenses provided by authors and poets.

ii) The second purpose is to give an overview of the entire series of lectures that makes up the complete Society through Literature module. I propose to commence with this second task before returning to the subject of Story and History.

It is appropriate to begin with our motto, since it is a small work of literature in its own right, and because it encapsulates the central position we give to literature within the overall scheme of our academic and strategic priorities. The Arabic is […] meaning, “Let none come among us except those who are concerned with adab and siyar and who seek beneficial knowledge”. The Arabic word adab is of paramount significance within the context of this module, and we explain it as follows:

Adab contains the meanings of 'courtesy', 'discipline' and 'literature'. Courtesy is certainly one of the foremost requirements of the student and teacher in their meeting together, but it is equally a vital feature of any civilised society at all levels, in the family and in the marketplace. It is nevertheless one of the first casualties of the modern age, or more accurately, the 'technique age', in which we live. When the barrier of courtesy is destroyed, then the road lies open to the barbarities to which we are increasingly inured.

Discipline is an essential ingredient in any endeavour, not least in the fields of teaching, training and learning which are of primary concern to us.

Literature is of paramount importance on a number of levels. Firstly, it cultivates and transmits the relationship to language without which all knowledge and science are reduced to technical applications and exercises in pragmatism; a road leading to destinations which include 'total war', 'collateral damage' and genocidal 'final solutions' the abhorrent instances of which we see being carried out with greater and greater efficiency almost daily. Secondly, it is through literature that great authors and poets have transmitted their deep insights into the inner drives, actions and reactions of the human being, and have recognised the workings of history and new directions whose stirrings we must also assist through literature and poetry amid the otherwise dismal landscape of world politics.

This module, therefore, is a direct expression of our ‘concern’ with literature within the meaning intended by our motto, and is a direct effort towards the exploration and examination of the many themes that are bound to arise out of so vast a reservoir of human culture and civilisation.

For the purposes of basic clarity what, then, is the ordinary definition of the word literature? The concise OED gives us the following:

1 written works, esp. those considered of superior or lasting artistic merit : a great work of literature.

2 books and writings published on a particular subject. 3 promotional leaflets and other printed materials used to advertise products or give advice.

Wikipedia gives us a little more to go on:

Literature (from Latin litterae (plural); letter) is the art of written work. The word literature literally means "things made from letters". Literature is commonly classified as having two major forms—fiction & non-fiction—and two major techniques—poetry and prose.

Literature may consist of texts based on factual information (journalistic or non-fiction), a category that may also include polemical works, biography, and reflective essays, or it may consist of texts based on imagination (such as fiction, poetry, or drama). Literature written in poetry emphasises the aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language—such as sound, symbolism, and metre—to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, ordinary meanings, while literature written in prose applies ordinary grammatical structure and the natural flow of speech.

It will become clear in the course of these lectures that apart from what we would ordinarily think of as literature, our scope will also be extended to encompass such literary expressions as academic writing, journalism, myths, legend, religious scriptures, song lyrics, opera libretti, hymns and qasidas (Arabic poems written in praise and remembrance of Allah and His Messenger and sung to the rhythm of traditional metres and melodies). The other major zone of literary endeavour which has come to prominence, if not dominance, in the twentieth century is that of film in its many and varied genres. It is now almost impossible for us to escape the influence of film on our perceptions of literature in the ordinary sense. There is no major work, certainly in the western literary canon, which has not been adapted for film, and no historical episode of any importance which has not been scripted, documented or dramatised for cinema or television.

This means that the way in which we perceive or ‘remember’ historical events has been profoundly influenced by what we have seen on our screens, and by the same token, the way in which we read, envisage and interpret well-known and important works of written literature is unavoidably affected by film adaptations. For example, who can honestly say that they can read a Jane Austen or James Bond novel without automatically seeing the faces and hearing the voices of the various actors and actresses whose screen portrayals have become inseparable from those stories and characters? Who can think of Shakespeare’s Henry V without Sir Lawrence Olivier or Kenneth Branagh coming to mind? This is without confronting the deeper question of what Shakespeare himself has done, for the sake of dramatic effect or narrative convenience, to influence, if not actually distort, our common understanding of key events and personages in British and European history. Is it possible to think of Lawrence of Arabia without being overwhelmed by the atmosphere created on film by David Lean and the dashing image of Peter O’Toole in the role of T.E. Lawrence? Once more, this is before we come to consider the effect such works have had on our collective impression of historical episodes such as the true role of British imperialism in the creation of the Middle East that we see today.

The very real impact of this phenomenon brings home to us the, perhaps justifiable, unease the majority of Muslims feel when confronted with the prospect of the representation on film or other visual media of the Prophet Muhammad (saws) and his Companions (ra), or any of the prophets in general. Thanks to the popularity of the film, The Message (1976), how many of us who watched it (perhaps repeatedly) have now fixed in our imaginations, perhaps permanently, the images of Anthony Quinn as Hamza (ra), Johnny Sekka as Bilal (ra) and Irene Papas as Hind? And what effect do such influences have on our personal engagement with the Deen?

It should be said from the outset that this particular course is somewhat unusual, and possibly quite unique, with respect to what may be expected from a standard academic offering. It is not the purpose of these lectures to teach literature, creative writing or to fill the yawning ‘gaps’ which many of us probably feel we have in our literary educations. It is certainly not the place to be if one is simply hoping to catch up with one’s Shakespeare, Dickens or Dostoevsky – although it is certainly the case, in keeping with the rapidly spreading ethos and practice of continuing education and lifelong learning, that participants will come away inspired to embark upon new literary directions, acquire fresh perspectives, undertake their own investigations and above all, to gain new insights into the nature of our own modern societies and circumstances. The best result will be the acquisition of beneficial knowledge that will be useful and effective in negotiating the challenges we all face in an increasingly confusing, self-destructive and suffocating world. Therefore, although there is no prior reading required, the expectation is that participants will depart with extensive and exciting new reading lists for their own further study.

The Society through Literature module has been constructed as a balancing act between the need to touch on a meaningful range of the key components of so called civilised society and culture as we know and experience it, and as it is reflected in the titles of the lectures, whilst also introducing alternative perspectives, raising questions and indicating solutions by means of exploring the lives of the various authors together with their works. Hence, under the circumstances of such an approach, the course makes no pretence at academic objectivity, and neither is it my intention at this point to enter into a lengthy critique of scientific method and its shortcomings; for this purpose I strongly recommend a thorough study of our module on Technique and Science which is available in its entirety through the Faculty. However, returning to the explanation of our motto and our choice of the expression [‘ilman nafi’a] ‘beneficial knowledge’ (which I have already used more than once so far in the course of this presentation) will allow us to sum up our point of view on the matter in brief:

The use of the term 'beneficial knowledge' is a necessary counter to the concept of academic studies for their own sake, since we have seen the transformation of the academic arena into a handmaiden of the powerful hegemonic political and economic forces of our age while yet maintaining the myth of scientific objectivity and academic detachment. In truth, we do not deny that the discipline of scientific method has its place but neither will we deny its limitations or the limitations of the dialectical method and gratuitous polemic as a means of philosophical enquiry. The Muslim Faculty will nurture a determination on the part of staff and students to actively engage in the vital issues of the age and to inspire a new generation to assume the mantle of responsibility for indicating and ushering in the necessary revaluations and transformations whose historical immanence we can sense, but whose emergence is otherwise neither guaranteed nor inevitable.

Therefore, let it suffice to say that the great value to us of many of the works that these lectures will broach lies in the fact that their authors are unconstrained by expectations of objectivity, on the contrary, it is the very spontaneity, the honesty and the introspective courage of the genuine artist (and for that matter also the philosopher) that offers us the reassurance that what they have found to be true of themselves, is also likely to be true of the rest of us to some degree or other, given the shared reality of being human and being in the world.

Whilst remaining uncompromising with respect to intellectual probity and rigour, this inevitable eschewal of academic objectivity is also reflected in the background and culture of the course lecturers. We all happen, so far at least, to be male (although this may change before the end of the course). With only a single exception so far, we were all born and raised in the West and received a typical western schooling and university education. Again, with only one exception so far, we all at various points in our adult lives consciously and freely chose to become Muslim. The majority of us have at different times and to various differing degrees, been exposed to the thought, teaching or influence, directly or indirectly, of the leading Sufi Shaykh, intellectual and man of letters, Dr Abdalqadir as-Sufi, whose extensive writings over the last fifty years or so have given rise to a body of work which, with respect to a comprehensive grasp of the twentieth century, might easily stand by itself as the clearest illustration of the approach to the enterprise of looking at society through literature that is aimed at in this module.

In other words, our aim will be to offer a mirror, or a kaleidoscopic view, through which it becomes possible to encounter, examine and interrogate our own political, artistic, psychological, spiritual and cultural reflection, not from the outside, but from deep within. However, the ongoing journey to the realisation of a lived and authentic Muslim experience and consciousness, and the deeply human nature of the literary endeavour are what provide this module with a unique viewpoint and a style, which in order to be at its most effective and revealing cannot afford to be obscured by unrealistic claims to objectivity, or obstructed by the opaque insulation of scholastic detachment. An almost identical plea in terms of intent was made by Martin Heidegger to the audience at his 1959 lecture, The Way to Language:

If we understand all that we shall now attempt to say as a sequence of statements about language, it will remain a chain of unverified and scientifically unverifiable propositions. But if, on the contrary, we experience the way to language in the light of what happens with the way itself as we go on, then an intimation may come to us in virtue of which language will henceforth strike us as strange. [On The Way to Language, p.111]

Therefore, rather than studying a ‘module’ we are embarking on a ‘course’ of lectures to be undertaken as a journey, with each lecture experienced as an event along the way, in the expectation that each one may tell us something unfamiliar and revealing. In the time that remains to us we should now turn to the specific theme of Story and History.

Story and History

In the context of any general examination of the role or impact of literature (in its broadest sense) on a society’s sense of identity, its culture and behaviour, it is essential that we remind ourselves of the immense importance of the ‘story’ or ‘narrative’ as a form of communication and indoctrination, and as a means for the transmission of ideas across both time and space. The power this medium possesses in terms of shaping or reshaping collective and personal histories, providing justification for political action and offering persuasive frameworks to support moral, ideological or even scientific standpoints, should not go unexamined.

Obvious politico-historical instances of the massive impact and endurance of such narratives (and there are literally too many to choose from) include the founding myths of nations such as the USA and Israel (to name two which are both rarely out of the media, are frequently linked together and whose political actions continue to have the highest profile in terms of their consequences for international affairs). The stories maintained by both of these states have served to justify at different times and on different scales, the slaughter and abuse of the prior inhabitants of their respective countries, and both have gone to great lengths ever since to reinforce these narratives through academic literature, journalism, documentaries, countless novels, children’s fiction and popular cinema and television. Even in the face of demonstrable evidence to the contrary and all of the confirmed results of historical research and revision, such well established narratives inevitably prove themselves to be extremely resilient and difficult to erase. The stereotypical American self-image of the intrepid and adventurous white-skinned cowboy, heroically battling his way out West (usually against the odds) braving the savage onslaughts of the bloodthirsty red man, persist in the psyche to this day thanks to the potent storytelling combination of popular literature and Hollywood films.

Films such as Little Big Man (1970), Dances with Wolves (1990) and The Last of the Mohicans (1992), all drawing on novels and/or earlier film treatments, may have been well intentioned with respect to redressing the balance to some extent, but what they all absolutely succeeded in ensuring is that however the story is told, it is the white American figure (invariably played by A-list Hollywood stars) who always emerges as the pivotal element (in these instances we refer to Dustin Hoffman, Kevin Costner and Daniel Day-Lewis respectively). Furthermore, the fact that historically and morally ambiguous individuals such as George Armstrong Custer, and attested criminals and murderers such as William H. Bonney (Billy the Kid) and Jesse James, can all emerge from their dubious histories and persist in the collective ‘memory’ as folk heroes, national monuments and cultural icons, stands as undoubtable testimony to the incredible power of these stories.

The line between fact and fiction becomes blurred as legends are created; fiction and propaganda are projected as fact, and so the storehouse of social history is hijacked. By the same token, the stories and narratives we are brought up on and live with are absorbed into the personal narratives which supply us all with the sense of identity and self-image which every individual relies upon to function confidently in society. Hence, as George W. Bush rose to meet the challenges of the 11th September 2001 attacks on New York and Washington D.C., as well as in the build-up to the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan and in the ‘Wanted Dead or Alive’ campaign in pursuit of Usama bin Laden and the top echelons of al Qaeda, it was all too easy for us to reference the confident swagger of the mythical frontiersman driven onwards by the manifest destiny of the American imperium, in his adopted speech patterns and mannerisms. To my mind this was more than just affectation or carefully calibrated PR strategy – it was a combination of second nature in the case of Bush himself, and utter confidence in the efficacy of these attitudes on the part of his advisors and handlers.

In the case of Israel, the rationale for its foundation and survival rests squarely upon the wide acceptance of a historical narrative that paints a biblical picture of age old persecution of the Jews and expulsion from their rightful homelands, resulting in the Diaspora and the subsequent episodes of oppression and vicious anti-Semitism in Europe over a number of centuries, culminating in the Holocaust of World War II. The perpetuation of the image of the Jews as victims and as an endangered population continues to underpin Israel’s claims to being a special case and deserving of exceptional treatment by America in particular, as the major world power, and by the rest of the western world in general. Jewish academics themselves over recent decades have begun to revise this powerful narrative. John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt state:

In that story, Jews in the Middle East have long been victims, just as they were in Europe. “The Jew,” Elie Wiesel tells us, “has never been an executioner; he is almost always the victim.” The Arabs, and especially the Palestinians, are the victimizers, bearing a marked similarity to the anti-Semites who persecuted Jews in Europe. This perspective is clearly evident in Leon Uris’s famous novel Exodus (1958) , which portrays the Jews as both victims and heroes and the Palestinians as villains and cowards. This book sold twenty million copies between 1958 and 1980 and was turned into a popular movie (1960). Scholars have shown that the Exodus narrative has had an enduring influence on how Americans think about the Arab-Israeli conflict. [The Israel Lobby p.79]

There can be no doubt concerning the unimaginable nightmare of suffering sustained by millions of Jews due to widespread and open anti-Semitism in Europe over a very long period leading up to Hitler’s unprecedented ‘Final Solution’. That all of this should have provided the Zionist movement with persuasive moral justification for the establishment of an independent Jewish homeland is a well known part of the story, but the Zionist claim that Palestine was “a land without people for a people without land” does not stand up to historical scrutiny. Nevertheless, it has entered the narrative and remains effective in the minds of many as part of the enduring mythical picture.

There are countless other examples of stories such as these, from the founding myths and legends of ancient civilisations across the planet, to other much more recent cases. However, what must remain central to this part of today’s lecture, is not so much the whys and wherefores or the ins and outs of accusations, recriminations and claims to human rights and social justice. We are primarily concerned with highlighting the potency of the story form itself and the impact of writers as creators of stories, and of literature as a medium for the dissemination of important narratives and as a permanent repository for their preservation, resurrection and authentication.

The universal presence of stories and storytelling as a fact of human cultural practice and education, suggests that as human beings we are psychologically predisposed to and mentally designed for this particular form of learning, memorisation and sharing information and experiences. The fact that storytelling is most efficacious and most readily given to being carried out in a social context, further underlines its fundamental connection to the natural human pattern of social living, transmitting knowledge and reinforcing common cultural bonds. Cognitive research confirms what we already know by intuition and personal experience, which is that we all love stories from a young age, that we follow them readily and attentively, that we find them easier to remember than other formats and that we all share a basic ability and tendency to resort to the story form whether in writing or in everyday conversation. A typical joke is nothing more than a very short (and hopefully) a very funny story. We are story-telling, and therefore, story absorbent creatures. Stories reflect the preferred shape of our human thought patterns in that we are given to thinking in narrative structures, whether it is about our own lives, trying to make sense of the world around us, or trying to remember a collection of facts. The following observations by the social historian Ivan Illich are at once enlightening and intriguing:

Silent reading is a recent invention. Augustine was already a great author and the Bishop of Hippo when he found that it could be done. In his Confessions he describes the discovery. During the night, charity forbade him to disturb his fellow monks with noises he made while reading. But curiosity impelled him to pick up a book. So, he learned to read in silence, an art that he had observed in only one man, his teacher, Ambrose of Milan. Ambrose practised the art of silent reading because otherwise people would have gathered around him and would have interrupted him with their queries on the text. Loud reading was the link between classical learning and popular culture.

Habitual reading in a loud voice produces social effects. It is an extraordinarily effective way of teaching the art to those who look over the reader's shoulder; rather than being confined to a sublime or sublimated form of self-satisfaction, it promotes community intercourse; it actively leads to common digestion of and comment on the passages read. In most of the languages of India, the verb that translates into "reading" has a meaning close to "sounding." The same verb makes the book and the vina [traditional stringed instrument] sound. To read and to play a musical instrument are perceived as parallel activities. The current, simpleminded, internationally accepted definition of literacy obscures an alternate approach to book, print, and reading. If reading were conceived primarily as a social activity as, for example, competence in playing the guitar, fewer readers could mean a much broader access to books and literature. [Shadow Work]

It is no accident therefore, that world literary culture is replete with well preserved myths, legends, fairytales and folktales, whose exact origins are often lost in the mists of time, but which continue to safeguard irreplaceable stocks of wisdom, morality, history and identity. What would the cultural narrative of Western Europe amount to without the Illiad and the Odyssey, Norse and Germanic legends or Celtic mythology? The same question can be asked with respect to the roots of regional or national cultural identities on every continent regarding the stock of mythical or semi-historical literature, whether oral or written, which underpins them.

Such myths are almost invariably connected to religious traditions and practices, which certainly in the Judaeo-Christian, Muslim and Hindu spheres of historical influence, have depended upon scriptures which have subsequently given rise to immense bodies of secondary literatures. That Muslims, Jews and Christians are collectively referred to in the Islamic tradition as ‘People of the Book’ – if you’ll excuse the predictable pun – speaks volumes! Having been brought up in a basically Christian home and Church of England boarding school environment, the fact that it has been over forty years since I have had any significant exposure to biblical texts or direct Christian teaching of any kind, and that twenty-five years have passed since I became Muslim, the biblical stories that I heard or read at Sunday school or in chapel remain fixed, whereas the thousands of sermons, lessons, chapters and verses have largely evaporated away. This is the power of stories. The Qur’an itself, by Allah (swt’s) doing and saying, has been made easy to remember in ways which go far deeper than its outward literary structure [Al-Qamar – 54:17; 22; 32; 40]. However, it is also worthy of note that a significant proportion of the Qur’an’s textual content consists of historical narratives related in story form.

Given the inherently persuasive power of the story form, it should not come as a surprise to find it being put to good effect more than ever on behalf of scientific theory, not only by the scientists themselves as they seek to make sense of their intuitions and hypotheses, but even more so by a wave of scientific popularisers ranging from enormously influential storytellers such as Sir David Attenborough (whose brilliantly constructed and narrated documentaries have probably done more to persuade us of Darwin’s evolutionary theories than any of the argumentation thrown at us by the likes of Richard Dawkins) to the daily and weekly diet of less impressive journeyman figures, who constantly appear in the media, but whose accounts possess a cumulative power of persuasion by virtue of the ubiquitous repetition of the stories they recount to us.

For example, earlier this week as I listened to the radio while driving into the city, I heard something which, were it not for the fact that preparations for this lecture had put me into a particularly alert frame of mind, I would simply have absorbed passively into a lifetime’s accumulated impressions of the accepted realities of the world we live in. The earnest commentator related various instances of how Darwin had succeeded in giving currency to his theories (whereas other scientists had failed miserably) by his use of everyday language, striking verbal imagery and simple narratives. As I listened, whether fortunately or otherwise, these examples reminded me of nothing so much as the famous ‘Just So’ stories invented by Rudyard Kipling.

That brings us to the end of today’s lecture. I have no specific further reading to recommend at this point, but I should remind you of what I mentioned earlier regarding the expectation of completing the course with an extensive reading list for future study. The following is merely a sample of some of the authors you should be prepared to encounter:

Ian Dallas (Collected Works)

Ezra Pound

Shakespeare

Ernst Junger

Martin Heidegger

Rainer Maria Rilke

Henrik Ibsen

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Gabriele D'Annunzio

Richard Wagner

Hilaire Belloc

Henry James

WB Yeats

Homer

Aeschylus

TS Eliot

William Faulkner

James Joyce

WH Auden

DH Lawrence

Ivan Illich

The subject of our next lecture is on Psychology through Literature by Abdalhamid Evans. Thank you for your attention. Assalamu alaykum.

Heidegger, M. On the Way to Language. Harper San Francisco, 1982

Illich, I. Shadow Work. Essays from CoEvolution Quarterly formed the basis for the book. Marion Boyars, 1981

Mearsheimer, J., and S. Walt, The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy. Penguin Group, 2007