Review

All lectures are freely available on this site.

6. Early Madinan Architecture and its Civil Society

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم وصلى الله على سيدنا محمد وعلى ءاله وصحبه أجمعين وسلّم

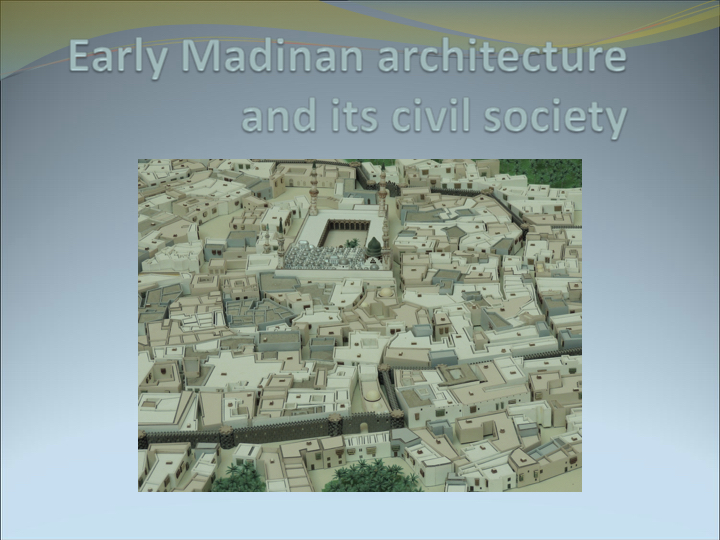

Title: Early Madinan Architecture and its Civil Society

Author: Mahmud Manning

Reader: Abdarrahman Heron

Publication date: 5th October 2013

Assalamu alaykum. Welcome to the Muslim History Programme of the Muslim Faculty of Advanced Studies. This is the sixth of 12 sessions which make up the Early Madina module. Today’s paper on early Madinan architecture and civil society has been prepared by Mahmud Manning who, unfortunately, is not available to present it in person. Therefore, the Faculty has invited me to deliver it on his behalf. The lecture will last approximately 40 minutes during which time you should make a written note of any questions that may occur to you for clarification after the lecture, which under the circumstances I will do my best to manage.

The aim of today’s lecture is to provide an overview of early Madina, touching on its geology & geography, its urban make-up and built forms. We will look at the general build construction of early Madina and the type of materials used. Additionally, it will look into the civic dynamic within the city in the light of the Revelation and the impact of the Social Charter which brought the pre-Islamic era of divisions and internal conflicts to an end; marking this new social contract as a model for future social stability.

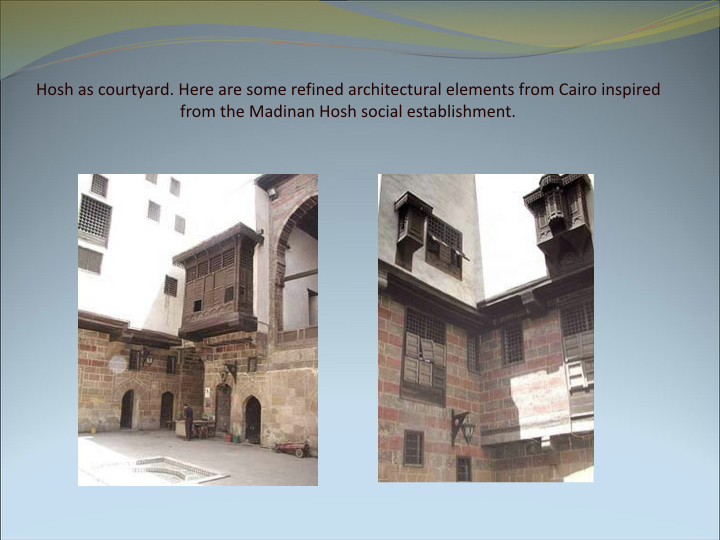

Furthermore, a specific examination of the functions of the ‘Hosh’ or enclosed public courtyard and its influence upon the way families lived, shared and socialised, will provide an ideal opportunity to reflect on and assess its potential for application in the context of community cohesion in today's wider society.

Early Madinan architecture and its civil society

[Figure 2]

[Figure 2]

When we consider a city; roads, streets, buildings and the architecture it contains, we think of shapes and heights, roads and so on, a tangle of activity and overlap. Here I want to present an overview so as to go towards the social dynamic of what it meant to live in early Madina. Not actually as architecture and blocks of stone or clay; but as a socially contracted agreement which brings out the ‘neighbourliness’ of living and a more socially intimate understanding of life lived in this primal city.

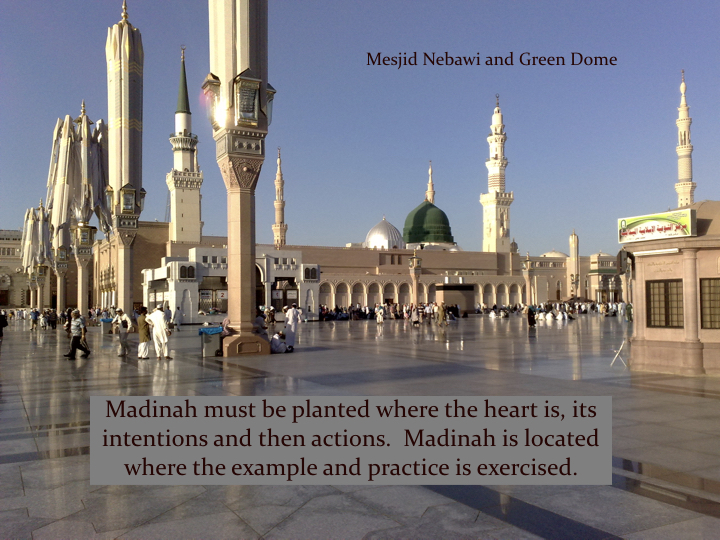

Firstly Madina must be recognised as the world’s archetypal and primal city. This is due to the abrogating nature of its governance tempered by revelation and prophetic example. So we must understand that it is not architecture and decoration which is of prime importance here but ‘Governed Justice’ which gives this city its singular position. When Justice is established through Muslim leadership (of taqwa and service), civic architecture, its building arts and extensions can then be brought out and expressed.

With this establishment, the city then becomes a place of celebration; celebrating the city’s social life, its industrious dynamic and creative expression. This industry and the natural skill of its people, as well as its natural setting expressed through the use of local materials, becomes an outward expression of what was contained within its first inward establishment! So it is the ‘himma’ and ‘niyyah’ the yearning and intention as a secret and a desire which is brought out and adorned within the succeeding generations.

Madina has never been a place of outward riches, like so many other wonderful Muslim cities; Samarkand, Delhi, Istanbul, Cairo or Fez. What it gives is a framework of law and compassion which allows these excellent social contracts to flower and then be expressed through architecture and the accompanying arts. Madina remained a quiet, gentle and small city, visited annually; the outer expansion of the ‘Ummah’ being brought back to the central core to be refreshed by it. Buildings remained in existence with little change, with many areas rebuilt onto this same footprint which exists even now. These footprints still show echoes of the streets, central meeting areas and the sizes of earlier building plots.

This governance was initiated through the ‘Sahifat al Madina’, the declaration of a charter which healed old divisions, jealousies and grievances within the existing tribes of the city and gave rights, responsibilities and protection to all people within Madina, including its Jewish and pagan tribes. It resolved conflicts and allowed all to participate, with views taken before the declaration was made and bound. It respected all property and ownership and initiated the compact of mutual defence against outside aggression.

This governance which ensured the protection of all its citizens extended out to trade and commerce, enhancing social relations as citizens, community members and extended family cohesion. The city’s name was then changed to ‘Munawwara’, to be known as the ‘Illuminated City’. This illumination then, is not due to street lighting and such devices but to the nature of the people contained within its streets. The hearts shone with the knowledge and action of the prophetic instruction. Of course we are talking about the great Sahaba, companions of our Prophet Muhammad (saws). So this means that the people were illuminated through the revelation received by Sayyiduna Muhammad (saws) and acted upon that teaching. May Allah, Subhana wa Ta’ala be pleased with all of them.

How was the city of Madina placed in terms geology and geography?

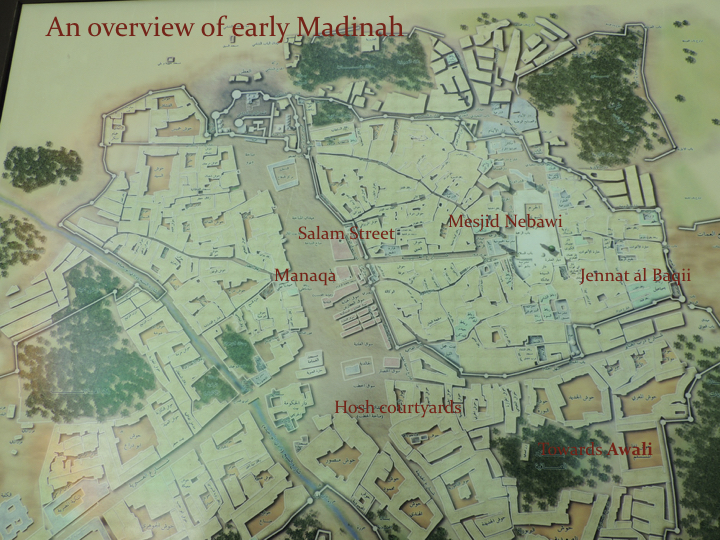

The city was situated upon an important trade route taking goods north and south to Sham and Yemen as well as east and west from Jeddah and the central Arabian Peninsula to the Arabian Gulf. Its specific siting was due to the presence of water close to its surface and the ability to support plant life and human settlement.

[Figure 3]

[Figure 3]

[Figure 4]

[Figure 4]

[Figure 5]

[Figure 5]

[Figure 6]

[Figure 6]

[Figure 7]

[Figure 7]

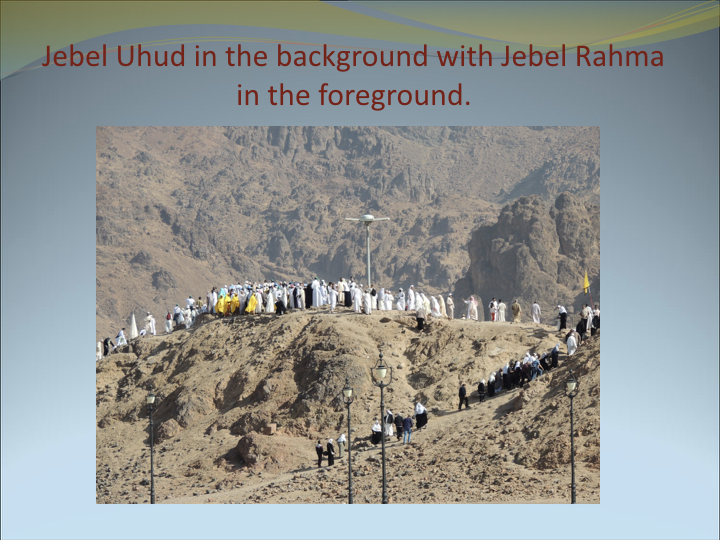

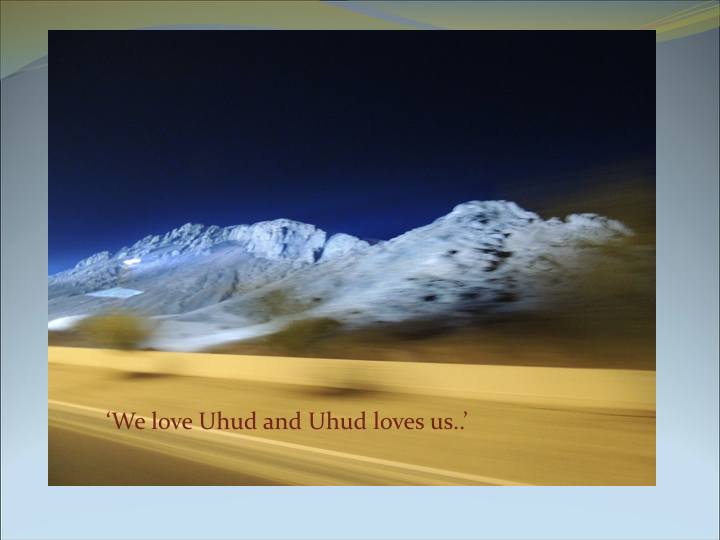

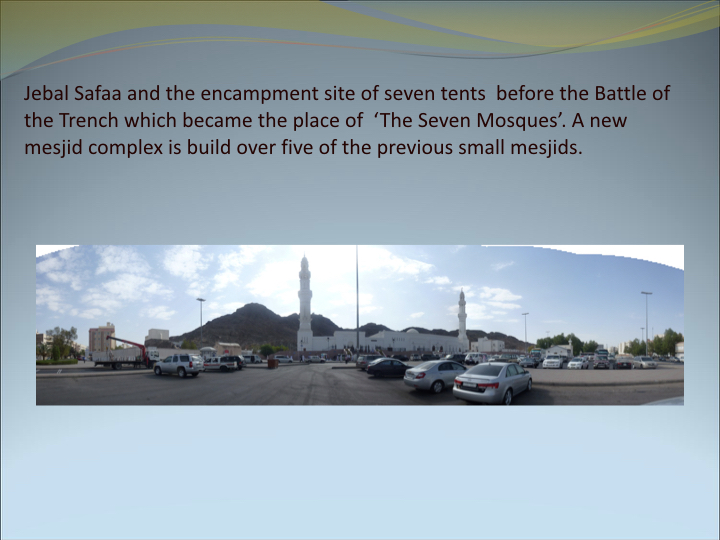

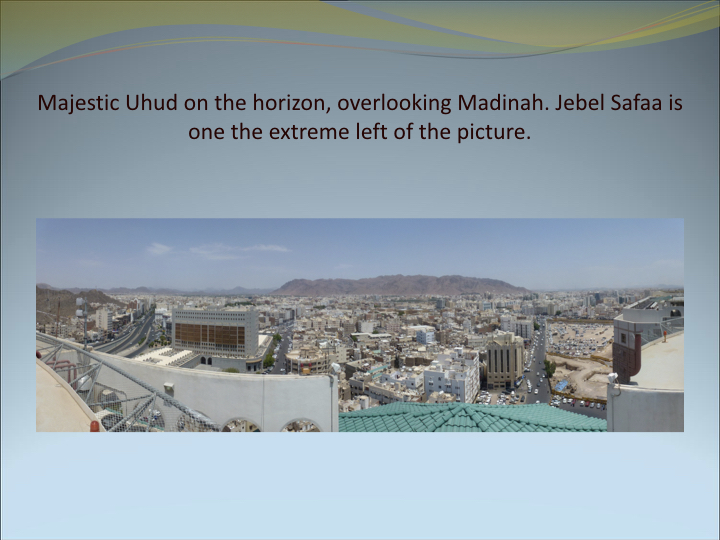

As an Oasis town within a harsh summer climate, it became a cultivated farming area, with extensive gardens and date palms; its buildings constructed from the nearby volcanic lava and clay earth. The city stands within an inverted bowl, a drainage area receiving rain-water run-off from the neighbouring and protective northern mountain of Uhud and the southern Jebal Ayr; [Figure 4] Jebel Uhud ‘which loves us and which we love, as it is upon the gates of Paradise’, and Jebel Ayr, a place ‘which hates us and which we hate, as it is upon the gate of Hell.’ [Figure 5] These are the dominant mountains. Smaller mountains are also within the city environs, Jebal Safa as a corner stone for the Battle of the Trench, [Figure 6] and the smaller hills of Jamalah which is located further northeast, resembling the humps of camels. [Figure 7]

[Figure 8]

[Figure 8]

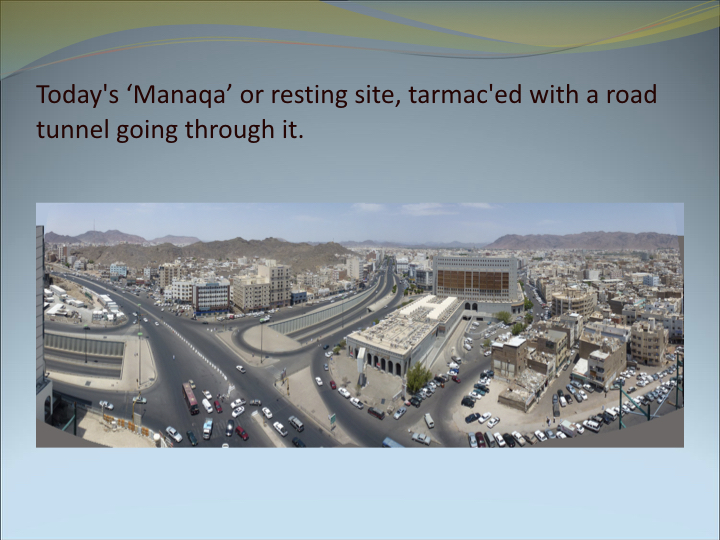

This star city had its main roads radiating out to further regional areas. [Figure 8] The central focal point was an empty space known as ‘Manaqa’ or ‘the place of rest and sitting’. It was the place of rest and sitting for camels upon their arrival in the city and also where the main market was established. This meeting point is close to the main Salam Street, which also became the main gateway for visitors to the Masjid Nabawi and its own entrance, Bab As-Salaam.

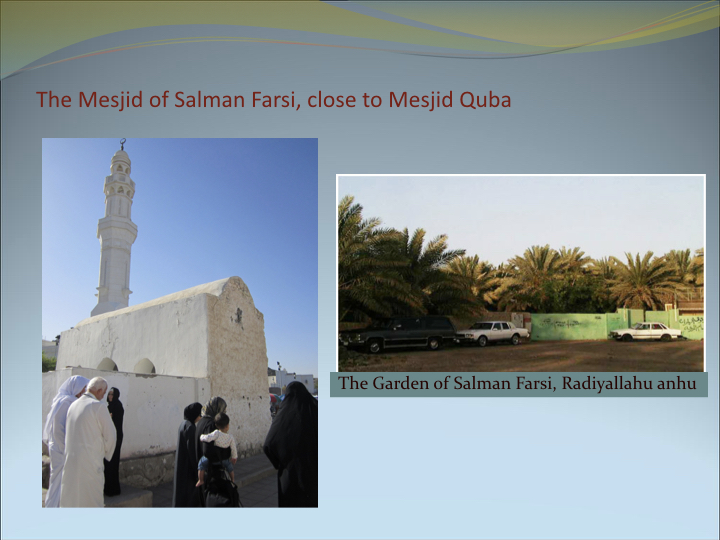

Two routes from the south bringing people from Jeddah and Mecca became established. The Quba Masjid, on this southern route, was founded by Sayyiduna Muhammad (saws) when the Hijra (or emigration) took place and the Muhajirun (the émigrés) were just reaching Madina and camped outside as night fell. Where the camp was founded became the site for the Masjid al Taqwa also known as Masjid Quba named for the small village at this location. The resting place of Qaswaa’ the she-camel of Sayyiduna Muhammad (saws), is also recorded within the masjid site.

[Figure 9]

[Figure 9]

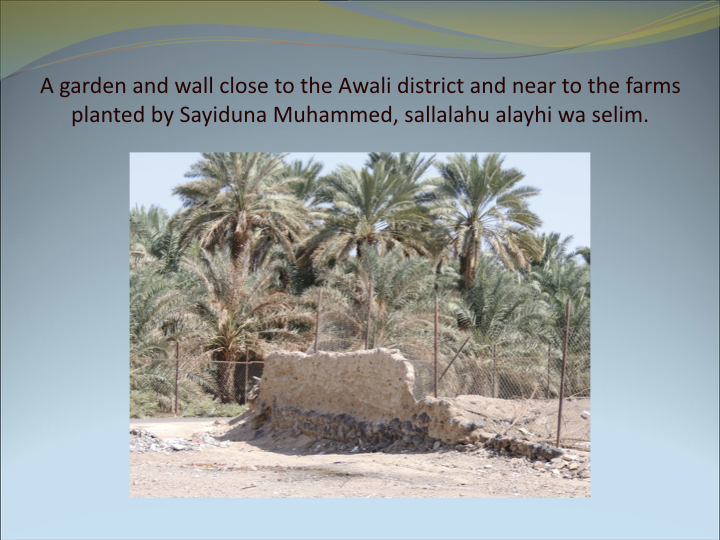

[Figure 9] Farmland close to the Awali district where Prophet Muhammad (saws) planted three hundred date palms to free Salman Farsi (may Allah be pleased with him) from slavery. It is located close to Masjid Quba. The companions collected the date palms from their own trees, (which are like saplings called ‘off-shoots) while Salman Farsi dug the 300 holes. Sayyiduna Muhammad (saws) then planted each tree by hand which all took root and thrived. [Figure 10]

[Figure 10]

[Figure 10]

Forty ounces of gold was also part of the price, instead a large nugget like an egg was given by Sayyiduna Muhammad (saws). As this still seemed a small amount to meet the weight asked for, Sayyiduna Muhammad took the gold piece and put it in his mouth, then gave it to Salman saying “Take it, and pay them the full price with it.” Salman weighed out to them forty ounces from it, and so he became a free man.

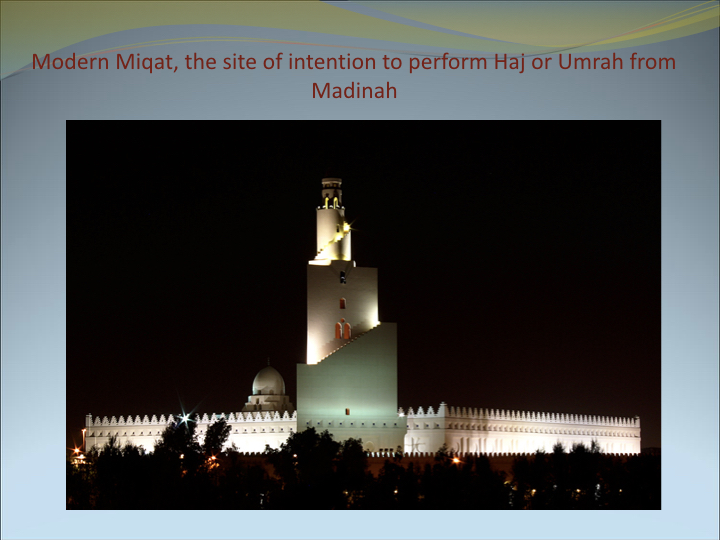

The second southern road became an outbound route to perform the annual pilgrimage and was known as Shari’a Uthman; a secondary parallel road is now used called Tariq Hegira. These pass close to the Masjid of Meekat, a point of intention to continue on the Hajj and Umrah from Madina. [Figure 11]

[Figure 11]

[Figure 11]

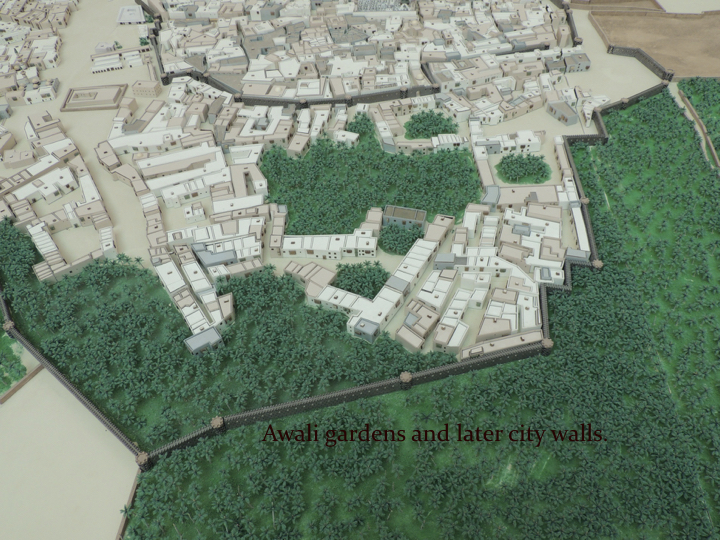

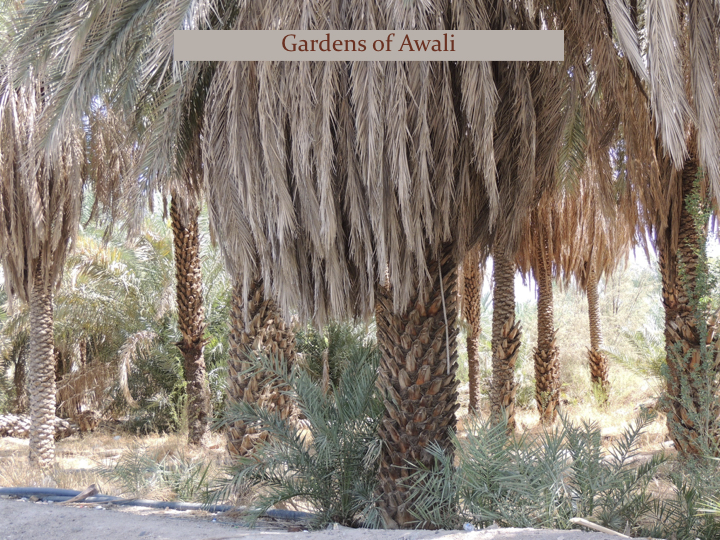

Close to the southern central area and next to the masjid of Sayiduna Bilal, may Allah subhanah wa Ta’ala be pleased with him, are the gardens of Awali. These enclosed gardens contain the date palms of the famous Ajwa variety, especially considered by Sayyiduna Muhammad for their health and healing properties. This was an area particularly liked by Sayyiduna Muhammad (saws) which he would visit with his family to enjoy the shade, fruits and respite from the harsh summer heat of Madina. [Figure 12]

[Figure 12]

[Figure 12]

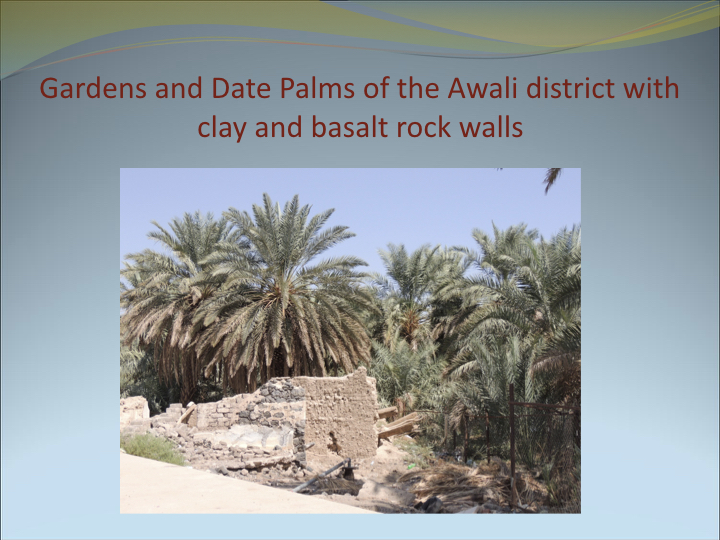

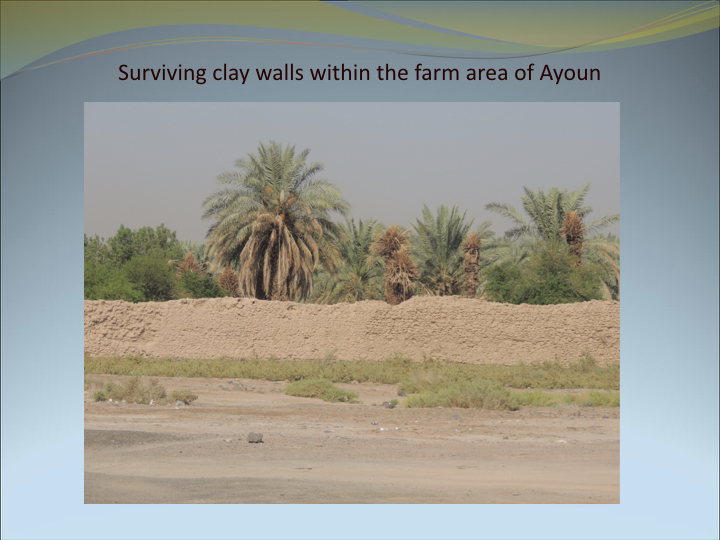

The Northern road also passes through extensive walled gardens and larger farms which are close to the area of Al AYOUN, which is a place of ‘two wells’ and famous for its sweet water. Farms were enclosed with basalt rock walls and completed with the available Madinan clay. Various local wall construction techniques were developed over the following centuries. [Figure 13]

[Figure 13]

[Figure 13]

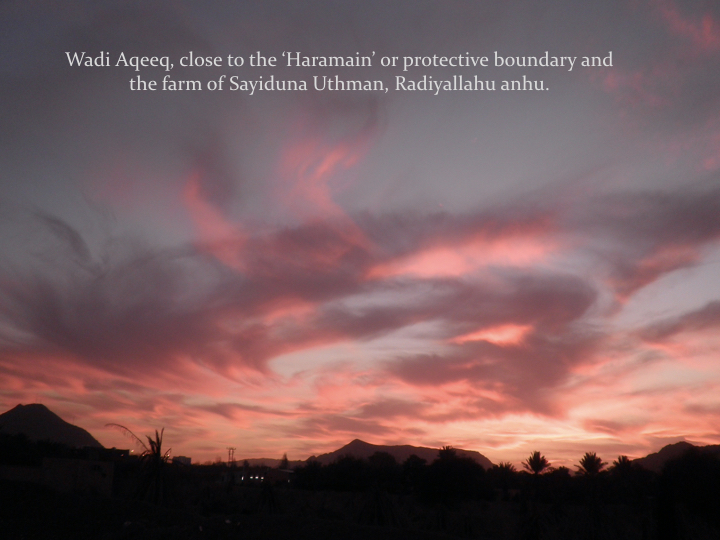

A deep wadi or dry river bed is present to the west of the city, known as Aqeeq, and floods from rainwater brought from the region of Taif, 150 km’s away. It is within the Haramayn, (the protected zone surrounding Madina) and remains a clear demarcation and boundary. [Figure 14] It is close to where the farm of Sayyiduna Uthman, may Allah be pleased with him, is situated. This farm was purchased to enable the easy access of fresh water to the early Muslim communities and poor people, its water was then sold at a fair and affordable price for all to purchase.

[Figure 14]

[Figure 14]

Building materials and types of dwellings

Madina as a city is known for the basalt lava which occurs within and alongside the city, extending considerably from north to south, (the Harrat Rahat) the result of a considerable volcanic eruption and lava flow in 654 (Hijri) which turned aside during its flow, narrowly missing Madina. Basalt was already used in early Madina from previous volcanic activity. There are also large outcrops of rock still in existence which are not all volcanic. This rock is without holes and dense. There are other small almost miniature mountains to the south of Madina, triangular peaks which are very striking, unique and unusual, protruding from the flat desert landscape.

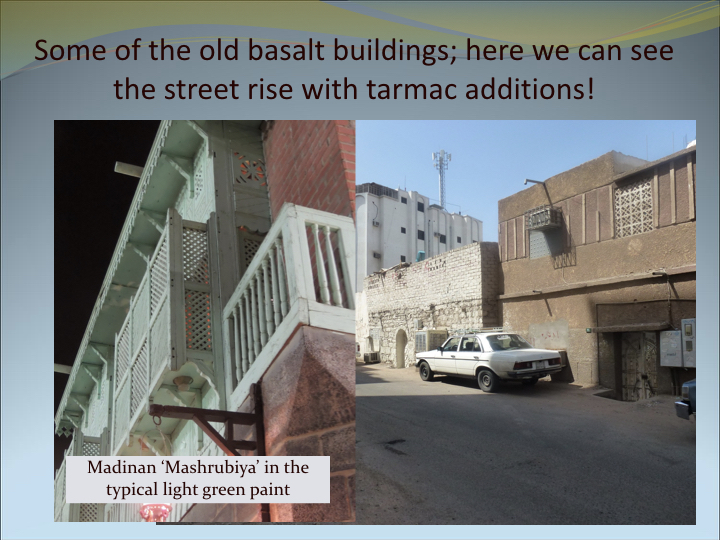

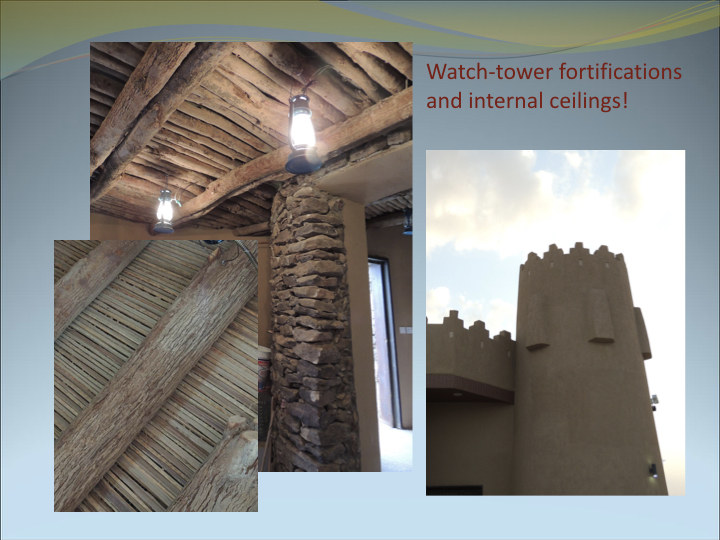

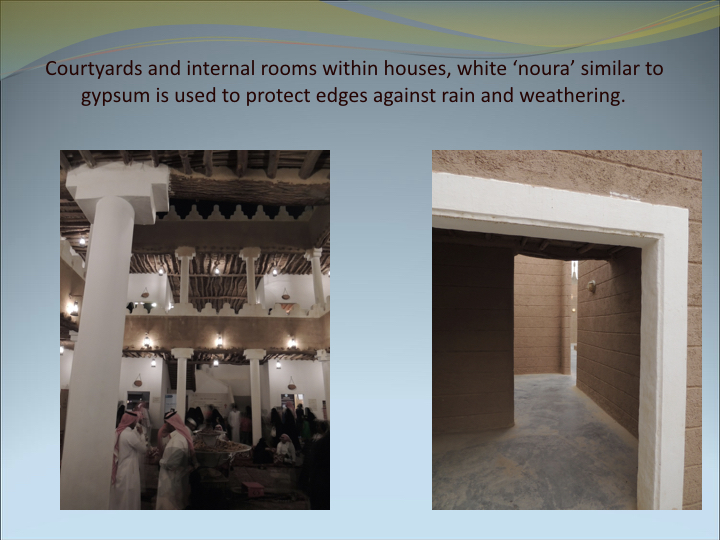

Early dwellings were built with the striking green clay of Madina. It is red earth clay, although when seen on the land it has a green colour to it! [Figure 15] Walls are constructed with flat roofs and are known as ‘Sageefah’ using date palm timber as supports. Palm leaves are bound together and are used on the roof. [Figure 16)] Simple hand-made clay bricks were also used for wall construction with a clay mortar. Stone lump foundations would also have been used. Later building construction is still simple; flat roofs with lump rock from foundation to first window height are completed with a clay wall rise. [Figure 17)] Future buildings are made completely of basalt and rise as single story buildings. In later centuries, dressed stone (cut with chisels) is used in construction. White gypsum called ‘noura’ is used to ‘cap’ walls as it is a type of lime which helps water flow off the walls without eroding them.

[Figure 16)]

[Figure 16)]

[Figure 15]

[Figure 15]

[Figure 17)]

[Figure 17)]

This overview has been a setting for a more intimate view and tasting of early Madinan life. As we considered that the importance of the city was in fact not its buildings but the people these buildings contained; so we will see that the activating dynamic, the ‘what we do and why’, and not the decorated artefact, remains important.

[Figure 18]

[Figure 18]

An important social aspect within the city was a unit type not bounded by family but by a collective of families not tied by blood. They became closely bound as neighbours which became by second nature an extended family. This unit was known as a ‘HOSH’ which can be translated with various meanings. The HOSH of Arabic can mean enclosed garden as well as ‘inside’ (as opposed to outside!!) but especially associated with an enclosed public space which accommodates various families.

The Hosh in Arabic, Persian and Turkish is aspirated (with a nokta, a dot above the letter) and becomes Hosh-geldin and Hosh-armadet, ‘You are welcome, meaning by extension, you are welcome inside’ so that non-family members are permitted entry. The ‘hosh’ as a plain ‘Ha’ without a nokta, is a courtyard with more than one entrance where various housing units share this semi public/private space. It is particular to Madina and to the Hejaz region including Mecca. It developed a quiet code of conduct which has existed up to and within the last 30 years.

All families are considered neighbours up to seven houses away in a circular fashion, thereby creating these overlapping circles of care and consideration. There was a strong obligation, not just a lip service to ‘neighbourliness’. Care of the sick, provision of food and awareness of those in need, as well as care and protection towards the young. These Hosh became centres of extended family life which maintained a semi-private aspect. All children could be overseen with authority by the people of each Hosh or courtyard.

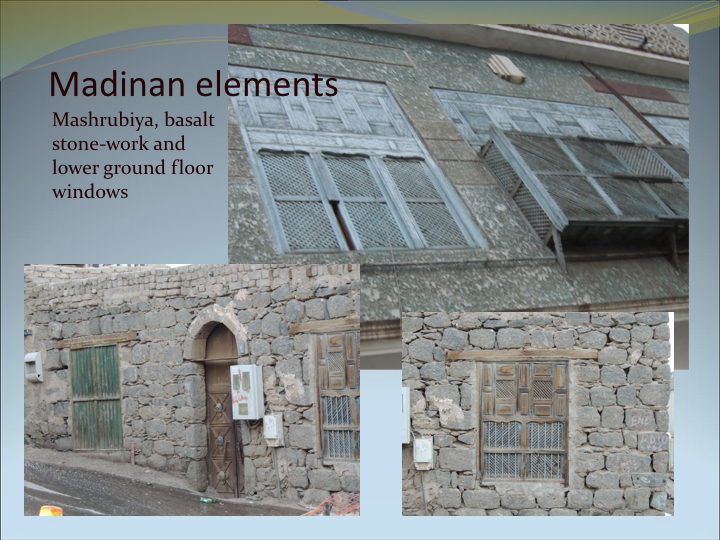

The older men may gather in the courtyard itself around benches, while women would be on the first floor rooms overlooking the courtyard, shouting out orders for errands to be carried out and noticing who came and went within the courtyard! The famous ‘Mashrubiya’ or wooden interlocked screens became an important architectural element within Madinan architecture; its light green paintwork signifying its place as Madinan (Madinan turbans are also either light green or brown). The Mashrubiya allowed viewers to look out, while breaking up views when seen from a distance; they also opened to allow better air ventilation.

Weddings occurred within the larger houses of each courtyard, and were provided without cost to those living in the smaller adjoining houses. It was a collective effort with everyone taking part. There was also no standard house, they were initially built according to the wealth of each individual family; aspects of ‘overlooking’ and privacy were governed and maintained through the building codes established by succeeding rulers. As families expanded further, rooms were built to accommodate the eldest son and his bride. If houses became vacant or available for purchase, then those within the courtyard had a right of first refusal, while newcomers who did enter to live within the Hosh/courtyard were vetted and elected in, they would have to meet with the approval of all the people within each courtyard.

The flat roofs would have been used for sleeping during the very hot months, as well as for drying goods and storing dried foodstuffs. Within these vicinities we can see that it became a closed unit of local privacy. A network of narrow twisting streets which blocked dust, produced shade and allowed air to travel through the walkways was gradually created. Open areas created meeting points where small masajid and convenient stores were placed. These twisting roads met larger streets which met the main arterial routes into the city and its main market area. Visitors were invited and brought into the courtyard; otherwise there was little reason for the stranger to venture there.

Madina has always been a city of welcome and hospitality to the guest. Indeed it was a high aim and a source of income for Madinan residents, welcoming and hosting travellers performing Hajj and Umrah. It became a time of sharing and learning, many ties of friendship existed and continued through generations, with visitors returning to their host families. It also gave rise to immigration and settlement. Many who travelled on the Hajj would stay, to be close to the Masjid of Rasull’ullah (saws). Nevertheless, the population of early Madina did not exceed 10,000 people; this rose to 30,000 people during the long Ottoman period.

The city was initially quite spread out; farms were fortified with watch-towers but without defensive curtain walls. The central area was gradually filled and then expanded with succeeding rulers, and a defensive wall was built 300 years from the initial Hijra or emigration with later walls built as the city expanded under different Mamluk and Ottoman authorities.

[Figure 19]

[Figure 19]

Lastly and most importantly, we must consider what this means in terms of our own sociability and society. What we do have are the keys to success, a model of example and implementation. It is either a tabula rasa of necessity or a collective willingness to commit to a community programme that is neither ‘villa separatism’ nor commune collectivist. As with so much within the Deen we can strike a balance which has been shown within Madinan society of private/semi-public shared residences; privacy is created, yet it is gentle and inviting.

The model for adoption as enclosed courtyard buildings with shared walls and open ‘skies’ can be adapted to various climates, the Haveli of Delhi being a great example of livability and artistry. This is also ‘good news’ for the concerned developers which show that height can be incorporated into contemporary build programmes; it is not necessarily a low build/ low density solution which does not address the high population densities of today.

What we must take is, in fact, what we must carry within us; architecture then responds to its location, available resources and climate etc. What is transforming is the social dynamic itself. So it is not Madina as location exactly but an inspiration to plant that Madinan seed wherever the intention for governed establishment is founded. It can be argued that it was the Magna Carta which enabled English society to expand through just governance, also the American Constitution of ‘the consent of the governed’ as expounded by the philosophy of John Locke. As Madinan Law is inspired through revelation and not revolution (!), we can see that the correct application of its principles will stand the test of any time, place or indeed people!

[Figure 20]

[Figure 20]

It is this ultimately which we take with us, armed with the Prophetic example and its declaration of protection and social welfare; enabling worship, protection of the weak, ability to trade equitably and the raising of healthy families.

In this sense every city and its people should strive to become ‘Munawwara’.

[Figure 21)]

[Figure 21)]

[Figure 22)]

[Figure 22)]

That brings us to the end of today’s lecture. For further reading I would recommend Precious Jewels in Describing the Features of the Prophet’s Holy City in the Prophet’s Era by Dr Abdul Aziz Kaki. The subject of our next lecture is Tribes and Families which will be presented in two weeks time by Hajj Idris Mears. Thank you for your attention. Assalamu alaykum.

Further Reading

Precious Jewels in Describing the Features of the Prophet’s Holy City in the Prophet’s Era by Dr Abdul Aziz Kaki. Private printing – 1431/34 978 603 00 4015 5